How to Measure Happiness

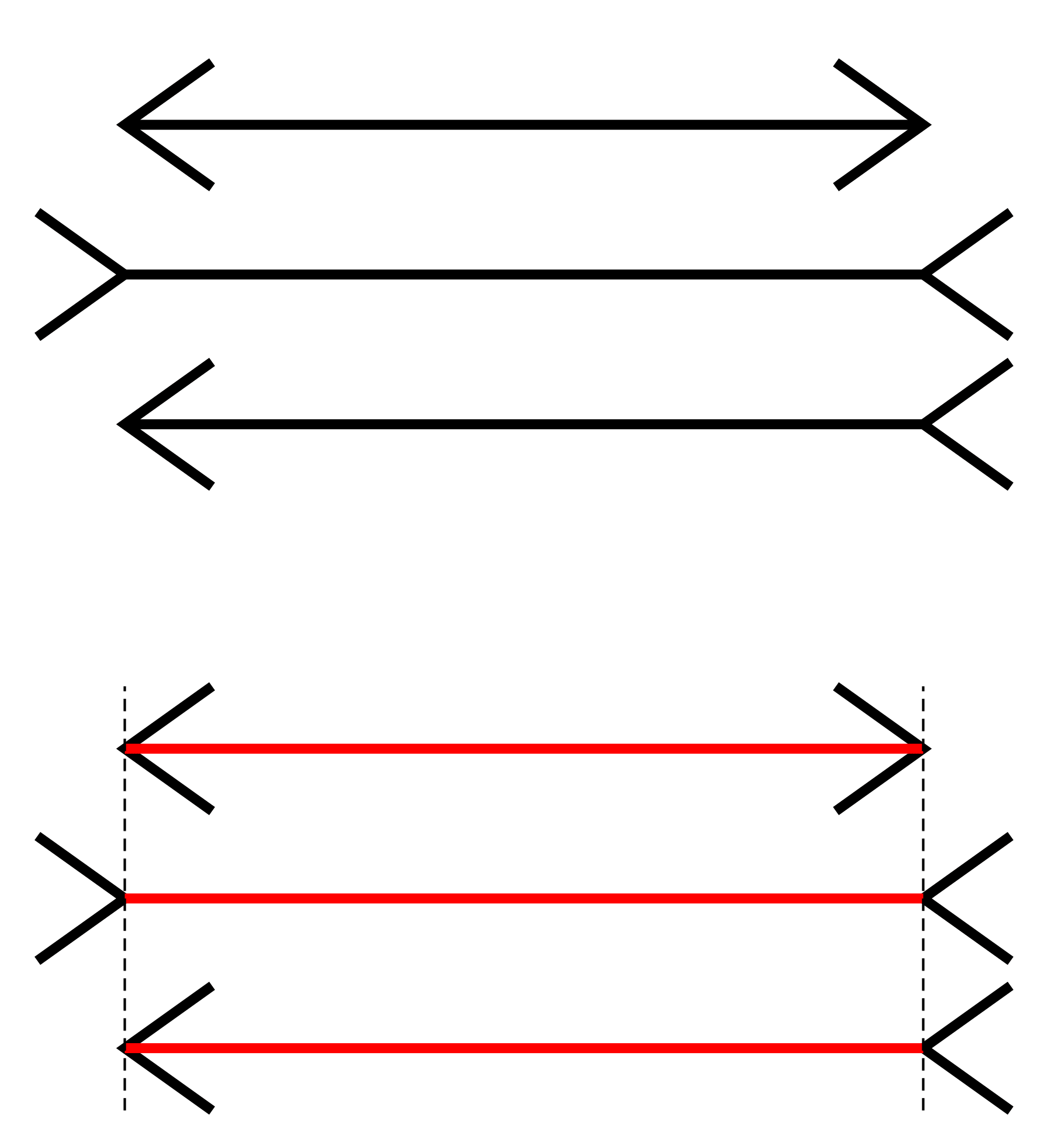

Anyone who has ever taught Intro Psych knows that one of the most popular lectures is the one that covers visual illusions. It’s easy to understand why. Illusions like the famous Müller-Lyer illusion shown below provide a clear example of times when our perception of the world is clearly, and demonstrably wrong. Although it’s almost impossible not to see the three lines as differing in length, simply removing the arrows at the ends shows that they are all, in fact, the same. It’s especially powerful when, as an instructor, you can explain why our sense of the world is so misleadingly wrong.

Fibonacci [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons

In happiness research, the closest thing we have to the power of these optical illusions is research that seems to show that people reliably and predictably misreport their levels of happiness. Specifically, there is a long line of research that purports to show that seemingly inconsequential events, like a sunny day or even just finding a dime on the ground, can lead to changes in happiness—changes that supposedly exceed the impact of unemployment, the onset of a disability, or winning the lottery (Schwarz and Strack 1999). The idea is that these inconsequential events don’t really impact happiness; they just cause momentary changes in mood, and people rely on their mood as information about how happy they are with their life as a whole. Thus, the report that they provide—and perhaps even the perception of their happiness—is an illusion.

Cece thinks she’s happy

Now I don’t really believe that the effect of these circumstances are really that large. Most of the original studies that find support for these effects use extremely small samples and flexible analyses. More importantly, there are now multiple, large-scale replication attempts that have failed to find evidence for the original effects (Klein et al. 2018; Lucas and Lawless 2013; Schimmack and Oishi 2005; Yap et al. 2017).

But these context effects—effects that challenge the reliability and validity of self-reports of subjective well-being—are not really the focus of this post. Rather, my focus is on the alternative measures that some have suggested should serve as a replacement to these global self-reports: experiential measures that are supposed to assess well-being in the moment using methods such as experience sampling.

The Logic of Experiential Measures of Subjective Well-Being

The problem with traditional global measures of well-being measures (it is said) is that it is too difficult and time consuming to think carefully about all the various aspects of life that one should consider when making such an evaluation. Therefore, people rely on heuristics, such as whatever information happens to be salient at the time of the judgment. If a person just happens to be thinking about a recent job success at the time the judgment is made, then that person might report higher well-being than if that person’s unsatisfying romantic relationship had instead been made salient.

To get around this problem, researchers have suggested that we should avoid measuring life as we think about it and instead focus on life as we experience it (Kahneman and Riis 2005). In other words, instead of relying on global judgments about how a person is doing as a whole, we should assess experiences from moment to moment, as they happen. Because it is quite simple for people to report how we are feeling at a single moment (you don’t have to remember anything or aggregate across domains or moments), then these experiential measures should be free of the biases and threats to validity that may show up in global, evaluative judgments. Kahneman (1999) even suggested that these measures are so simple and straightforward that we should consider them to be something close to a measure of objective happiness. In other words, when we use experiential measures, we get closer to revealing the red lines in the Müller-Lyer figure above: We strip away the illusory context effects to reveal what people actually think about their lives.

Experience Sampling Versus the Day Reconstruction Method

Now unfortunately, true experiential measures, as their name implies, require respondents to report about their experiences as they happen. And because experiences vary considerably from moment to moment, it is necessary to do this many, many times if we want to get a stable estimate of how a person’s life is going. This fact makes experiential measures more burdensome than standard, global measures, both for respondents and researchers alike. Even with the improvements in technology that have occurred over the past decade, this burden is still high. This means that incorporating experiential measures into large-scale research projects is often difficult to do.

Because of this limitation, researchers have developed alternative procedures that attempt to capture the rich data of experiential measures without requiring participants to answer questions repeatedly over an extended period of time. Specifically, Kahneman et al. (2004) proposed the Day Reconstruction Method as a less burdensome alternative. In this approach, respondents reconstruct their experiences from the prior day, breaking them down into specific episodes. Respondents then provide details about each episode, including what they were doing, who they were with, and how they were feeling. The idea is that it should not be so difficult to remember the details of recent, concrete episodes, and thus, the DRM should be able to duplicate the information that one would obtain from the more burdensome ESM.

But Does It Work?

The critique of global measures that researchers like Kahneman, Schwarz, and Strack have put forth seems so simple and elegant, and the ways that experiential measures solve these problems seems so clear, that it almost seems like actual tests of validity are not needed. Indeed, the DRM has been incorporated into some pretty important studies (like the American Time Use Survey, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, and the German Socio-Economic Panel Study1) without much evidence that the DRM actually does what it is supposed to do. For instance, in the original Science paper introducing the method, Kahneman et al. (2004) never presented any data that compared ESM and DRM reports from the same participants over the same period of time. And as far as I can tell, only a couple small-sample studies have done so since the publication of this initial work.

Because of that, my colleagues2 and I decided to take a look at how well these two methods converge (preprint just released here; at the time of this post, this has not yet been submitted, so comments are welcome). In two studies, we asked undergraduate participants to complete a day of ESM, followed by a single DRM that covered the same period. We then matched moments across methods to see whether reports of affect and situational experiences agreed. And did it work? Well, that depends on exactly what question you are trying to answer.

First, the Good News

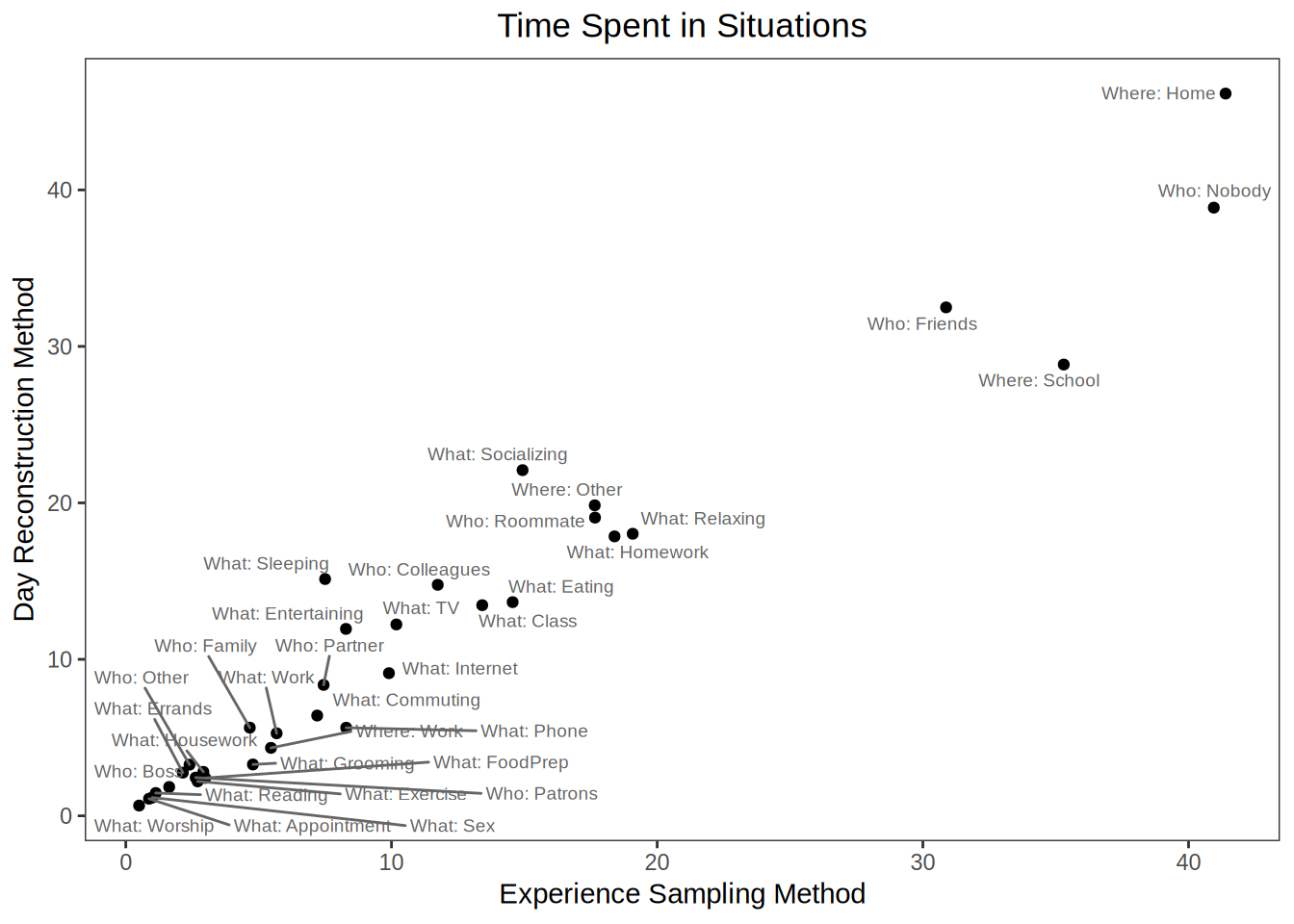

If you just want to know how much time people spend in different types of situations then you get pretty similar results across the two methods. Across all situation variable we measured, the estimates correlated r = .97. Here’s what a plot of those estimates looks like:3

It’s kind of fun to see what students do with their time; but the important thing for us is that the picture one gets is pretty similar regardless of the source of the data.

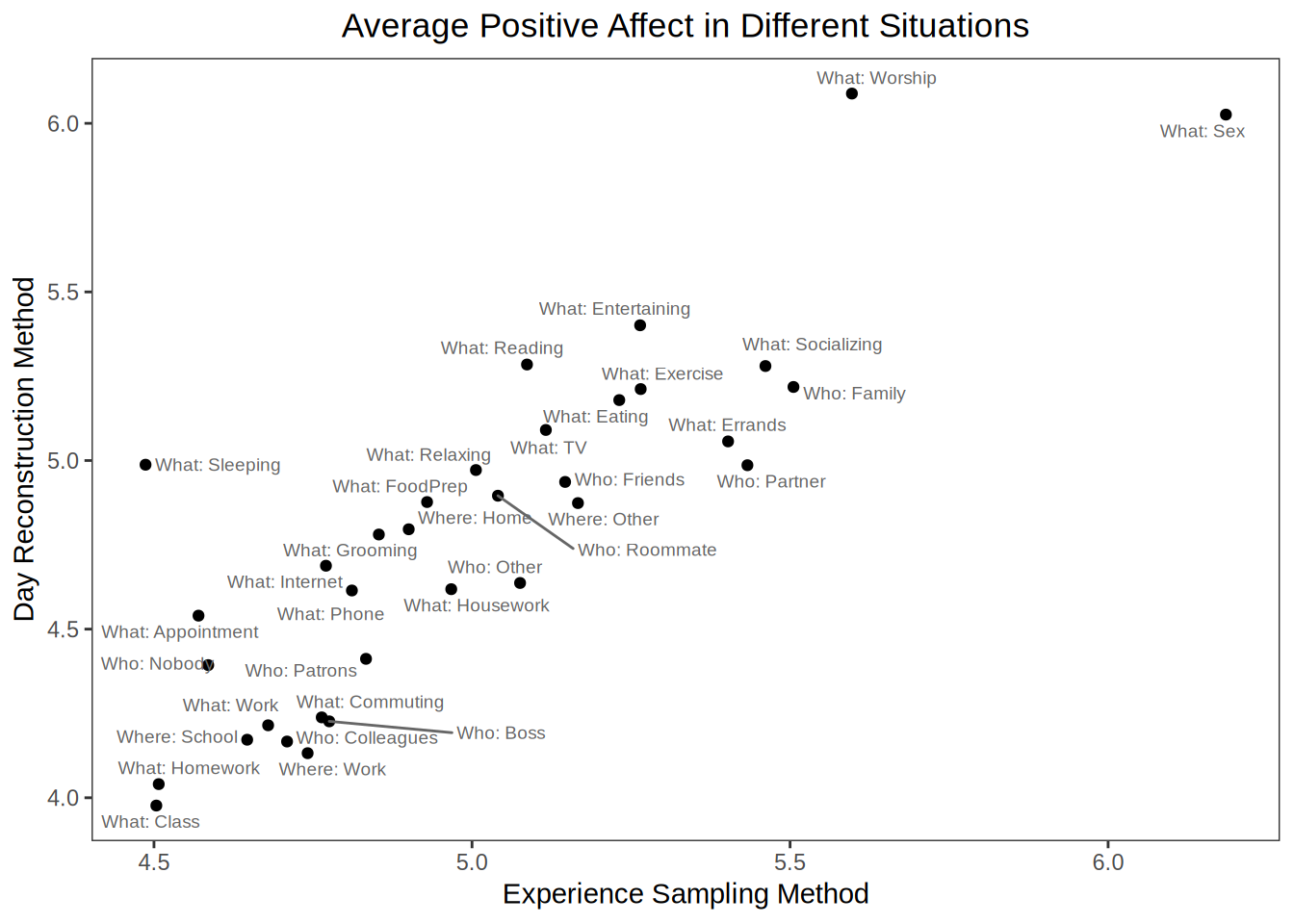

Similarly, if you want to just look at which situations are most enjoyable, you get similar information from the two approaches. The correlation between average positive affect reported for each situations as estimated by the two methods is r = 0.85. Again, here’s a plot from Study 1:

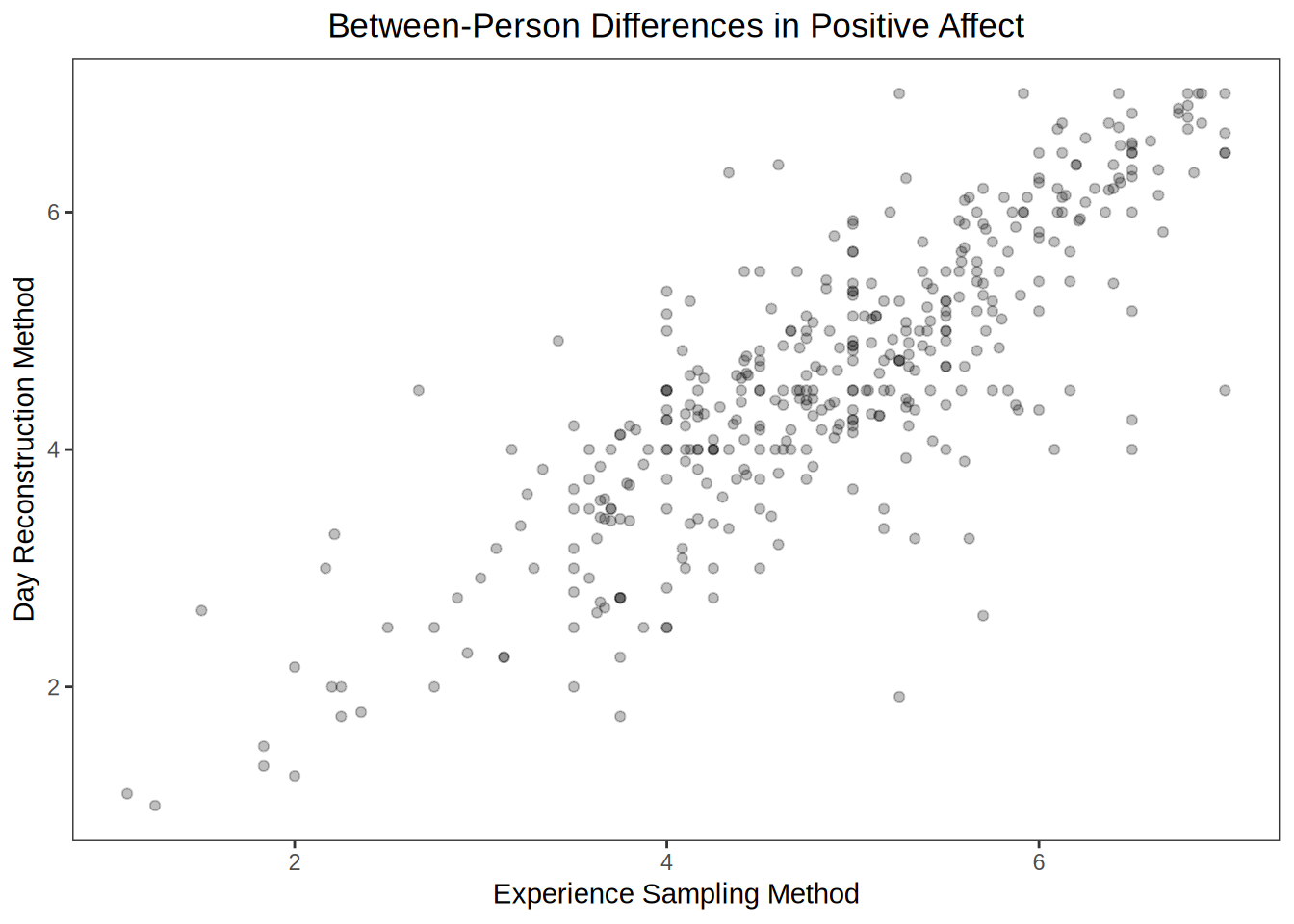

Finally, even if we want to move beyond the situation level, we find some decent cross-method agreement. For instance, if we want to know how happy people are over the course of an entire day (in other words, if we want to look at between-person differences in average affect), then ESM and DRM give us pretty similar results. In this case, the correlation is r = 0.83 (data plotted below). Everything looks good so far.

Now the Bad News

It turns out that cross-method correspondence isn’t always so good. Although estimates of person-level affect converge, correlations between the two estimates of time-use are not quite as strong. If we calculate the average amount of time that each person spends in each type of situation, the correlations are only moderate, ranging from very low (r = .05 for time spent eating) to pretty high (r = .78 for time spent with one’s boss), with an average correlation of .50.

Even worse, when we start to look within-persons over time, things start to get really bad. Now remember, although experiential measures were developed in part to address concerns about global self-report measures, they are also thought to be useful because of the incredibly rich data about within-person changes that these measures can provide. By having people report on their experiences multiple times per day, it is possible to track changes in well-being from moment to moment and then link these changes to the situational factors that people experience. But how do we validate these within-person reports? One way is to look to see whether two measures that purport to tap this within-person variance converge.4

In both studies, cross-method agreement was disappointingly low, both for ratings of affect and situational experiences. For instance, average within-person correlations between the two methods of assessment ranged only from .31 to .36 for positive and negative affect across the two studies. Average within-person kappa coefficients for dichotomous situational variables were also low, with an average of just .34 and .29 in the two studies. This means that we might get very different answers about how a person’s subjective and objective experiences have changed over the course of the day, or how those objective and subjective experiences relate to one another, depending on whether we rely on ESM or DRM.

To be fair (and as we discuss in length in the paper), these correlations are derived from a relatively small amount of within-person data. It is possible (though not certain) that with multiple days of assessment, these associations would improve.5 But again, it’s important to point out that one reason why the DRM has been incorporated into so many large-scale studies is that it can be administered in a single session, which means that a single day of DRM is often what is possible. So I think our study provides a pretty realistic picture of the convergence one would get from these methods as they are typically used.

Wrapping Up

In my experience, I’ve found that people are quick to criticize global self-reports of subjective well-being. Many of the concerns are well-founded, and I agree that there are lots of reasons to be skeptical of these self-reports. Research on well-being will be improved by taking these measurement concerns seriously. Yet at the same time, I’ve seen some people adopt alternative measures—measures that clearly address one or two potential problems of global self-reports—without applying the same level of skepticism regarding the psychometric characteristics of these alternatives. I think that, to some extent, this has happened with experiential measures like the DRM. People often adopt these measures without asking important questions about whether they really do what they say they do. At the very least, the data from our two studies suggest that the DRM may not be tapping the same information as the ESM, which should lead to some concerns about the validity of measures derived from the DRM. In fact, I think there are some reasons why measures like the DRM—and perhaps even the ESM—might be worse than global measures for assessing subjective well-being. But I’ll save those concerns for my next post.

References

Kahneman, Daniel. 1999. “Objective Happiness.” In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, edited by Daniel Kahneman, Ed Diener, and Norbert Schwarz, 3–25. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman, Daniel, Alan B. Krueger, David A. Schkade, Norbert Schwarz, and Arthur A. Stone. 2004. “A Survey Method for Characterizing Daily Life Experience: The Day Reconstruction Method.” Science 306 (5702): 1776–80. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103572.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Jason Riis. 2005. “Living, and Thinking About It: Two Perspectives on Life.” In The Science of Well-Being, edited by Felicia A. Huppert, N. Baylis, and B. Keverne, 285–304. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Klein, Richard A., Michelangelo Vianello, Fred Hasselman, Byron G. Adams, Reginald B. Adams, Sinan Alper, Mark Aveyard, et al. 2018. “Many Labs 2: Investigating Variation in Replicability Across Samples and Settings.” Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 1 (4): 443–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918810225.

Lucas, Richard E., and Nicole M Lawless. 2013. “Does Life Seem Better on a Sunny Day? Examining the Association Between Daily Weather Conditions and Life Satisfaction Judgments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104 (5): 872–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032124.

Schimmack, Ulrich, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2005. “The Influence of Chronically and Temporarily Accessible Information on Life Satisfaction Judgments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (3): 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.395.

Schwarz, Norbert, and Fritz Strack. 1999. “Reports of Subjective Well-Being: Judgmental Processes and Their Methodological Implications.” In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, edited by Daniel Kahneman, Ed Diener, and Norbert Schwarz, 61–84. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Yap, Stevie C. Y., Jessica Wortman, Ivana Anusic, S. Glenn, Laura D. Scherer, M. Brent Donnellan, and Richard E. Lucas. 2017. “The Effect of Mood on Judgments of Subjective Well-Being: Nine Tests of the Judgment Model.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113 (6): 939–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000115.

I admit to being somewhat responsible for the last of these.↩︎

Carol Wallsworth, Ivana Anusic, and Brent Donnellan.↩︎

These results are from Study 1 of our paper; Study 2 looks pretty similar.↩︎

And yes, we should expect these to be lower than the between-person correlations because much of the random measurement error in the momentary assessments is averaged out when aggregating; but these still seem low to me.↩︎

We’re working on that now.↩︎