The Rules of Replication: Part II

Cece doesn’t understand the rules of the couch.

Do replication studies need special rules? In my previous post I focused on the question of whether replicators need to work with original authors when conducting their replication studies. I argued that this rule is based on the problematic idea that original authors somehow own an effect and that their reputations will be harmed if that effect turns out to be fragile or to have been a false positive. In this post, I focus on a second rule, one for which my objections may seem more controversial, at least to those who already agree that replications are valuable.

Rule #2: Replication Studies Should Only Be Published if Manipulation Checks Are Successful

At first glance, this seems like a good idea. The rule is designed to ensure that the replication studies that make it into the literature are done well. There is always a chance that the researchers who choose to take on a specific replication project will not be qualified to conduct the study, or that something else will go wrong to prevent a particular study from providing a good test of the original finding. At a time when many critics of replication studies rely on vague concepts of “flair” or other unobservable forms of researcher expertise as justification for their dismissal of failed replications, the suggestion to use prespecified and verifiable indicators of the quality of a study is, of course, a good idea. As this thread from Sanjay Srivastava makes clear, setting up verifiable criteria shifts attention away from the investigator and back on to the qualities of the study itself:

“Is expertise important, yes or no” is the wrong debate 1/ https://t.co/Hi6JHGKWjG

— Sanjay Srivastava ((???)) May 3, 2017

Furthermore, even guidelines for registered replication reports (guidelines that are often written by advocates of replication) often stipulate that the final report will only be published if various quality checks like this are passed. However, ritualistic adherence to this rule can be problematic.

To provide a little context, I’ll focus on a specific set of studies that my colleagues1 and I recently published. Our paper reports nine attempts to replicate a classic finding by Schwarz and Clore (1983). This original study showed that life satisfaction judgments can be strongly2 influenced by transient and inconsequential factors like one’s mood at the time of the judgment.3 This original study manipulated mood in one study by asking participants to write about positive or negative life events and in a second study by contacting them on days with pleasant or unpleasant weather. Follow-up studies by these authors used additional mood manipulations including arranging it so that participants would find a dime on a copy machine (Schwarz 1987), by contacting people after their favorite soccer team won a game (Schwarz et al. 1987), or by having participants complete a task in a pleasant or unpleasant room (Schwarz et al. 1987). The original report of this phenomenon is one of the most cited papers in social psychology and was even nominated as a “modern classic” (Schwarz and Clore 2003), yet there are few if any replications conducted by researchers other than the original authors.

Because I use life satisfaction measures in my own research, this finding—which challenges the validity of these measures—has implications for my own and my colleagues’ research. And because we wanted to understand these implications more fully, we set out to replicate it with larger samples to obtain more precise estimates of the size of these effects.4

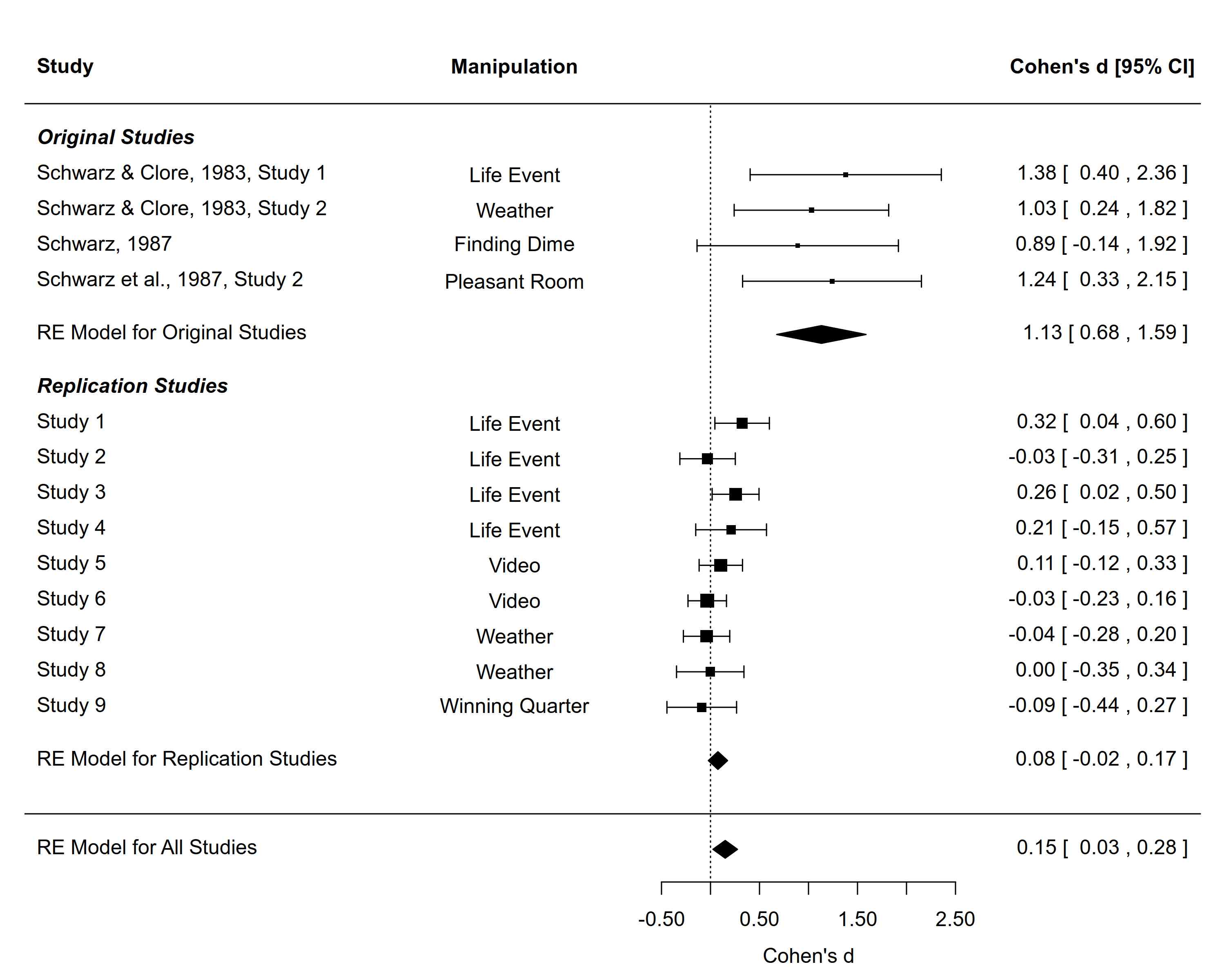

Long story short, our results were quite different than what was found in the original studies. Here’s a forest plot from a meta-analysis of the original studies compared to our replication attempts:5

And if you want to download our data to check these results yourself, feel free to visit our OSF Page, or just run the following code in R to instantly download all the data yourself:6

library(httr)

## Get Data from OSF Page: https://osf.io/38bjg/

## Study 1

data <- GET('osf.io/qxbs2//?action=download',

write_disk('study1.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s1 <- read.csv('study1.csv')

## Study 2

data <- GET('osf.io/gdpqm//?action=download',

write_disk('study2.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s2 <- read.csv('study2.csv')

## Study 3

data <- GET('osf.io/drpkc//?action=download',

write_disk('study3.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s3 <- read.csv('study3.csv')

## Study 4

data <- GET('osf.io/m59bx//?action=download',

write_disk('study4.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s4 <- read.csv('study4.csv')

## Study 5

data <- GET('osf.io/n78r3//?action=download',

write_disk('study5.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s5 <- read.csv('study5.csv')

## Study 6

data <- GET('osf.io/9bpuq//?action=download',

write_disk('study6.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s6 <- read.csv('study6.csv')

## Study 7

data <- GET('osf.io/pzqj2//?action=download',

write_disk('study7.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s7 <- read.csv('study7.csv')

## Study 8

data <- GET('osf.io/z5jgp//?action=download',

write_disk('study8.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s8 <- read.csv('study8.csv')

## Study 9

data <- GET('osf.io/nr4ps//?action=download',

write_disk('study9.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

s9 <- read.csv('study9.csv')

## Meta-Analysis

data <- GET('osf.io/6fs3v//?action=download',

write_disk('meta.csv', overwrite=TRUE))

meta <- read.csv('meta.csv')

If you take the time to read our paper (or to rerun our analyses yourself), you will see that of the nine studies we conducted, the manipulation checks were only significant in four: Studies 1, 3, 5, and 6 (results for Study 2 were mixed). So would our paper be better if the published version only included these four studies? There are three reasons why I think it would not.

Sampling Error Affects Manipulation Checks, Too

We often worry about publication bias, especially as it affects our understanding of effect sizes. When statistical significance is used as a filter for publication, then published effects will overestimate the true effect. Although there are important reasons to think carefully about manipulation checks when interpreting primary analyses, a blanket rule that excludes all studies from the published record when manipulation checks fail also serves as a significance filter that can distort effect size estimates. Importantly, this will affect estimates of the target effects (i.e., the effect of the mood induction on life satisfaction judgments) as well as estimates of the effects of the manipulation on the intervening variable (i.e., the effect of the manipulation on mood). Getting better estimates of both effects is important for planning future studies that will use these specific manipulations.

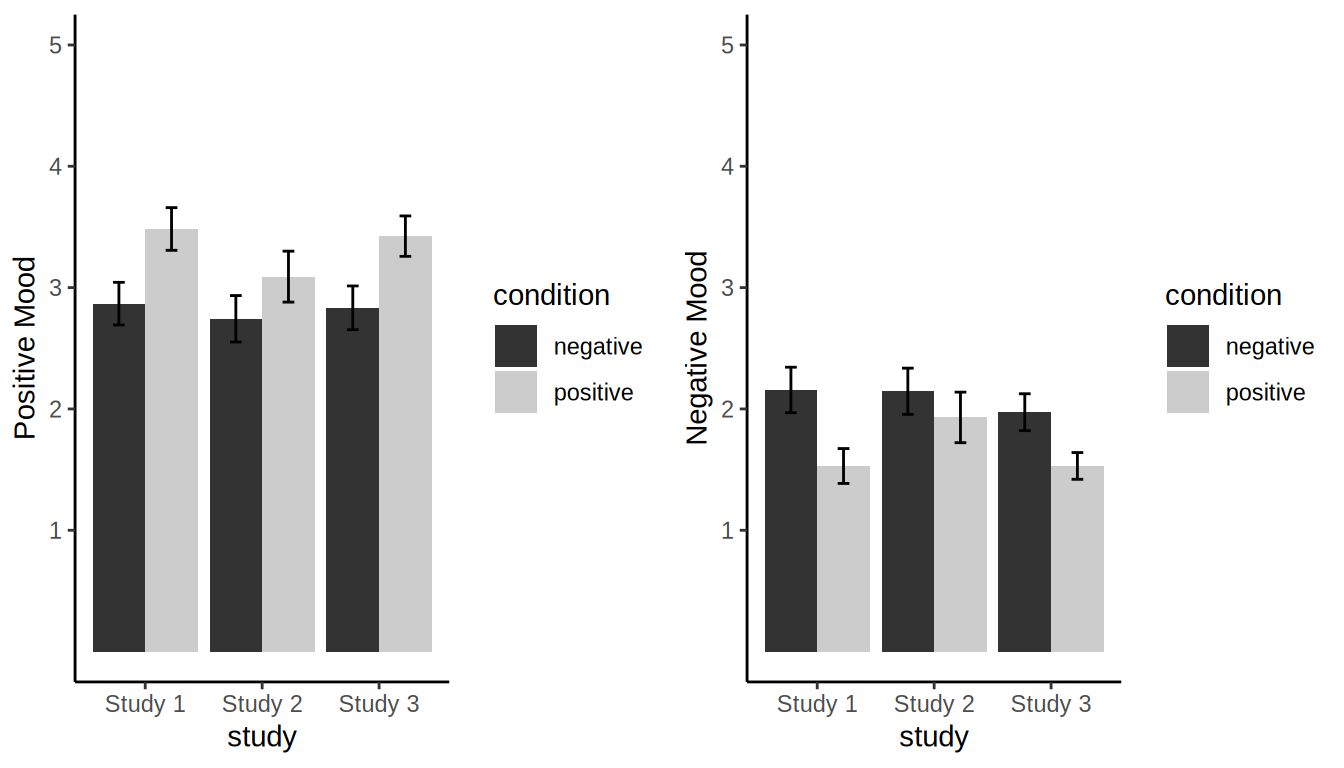

Consider the manipulation-check results from Studies 1, 2, and 3, which are pretty much exact replications of one another. As can be seen in the figures below, the results are weaker in Study 2 than in Studies 1 or 3, and the manipulation check for negative mood in Study 2 was not significant.

But should we conclude that we did something wrong in Study 2, or is this the type of variability in effects that we should expect when running three exact replications of the same study? If one purpose of manipulation checks is to show that the researchers who conduct the studies are competent and the specific procedures used can work, don’t Studies 1 and 3 accomplish this goal? Perhaps something did go terribly wrong in Study 2, but without direct evidence that such problems occurred, it seems better to report these results and to consider the fact that the manipulation check failed when interpreting the broader results. As long as the results are available, one can examine the effect of including or excluding these studies in meta-analytic averages (as we did in our paper).

Furthermore, if we wanted to plan for future studies, would we be better off using the meta-analytic estimate from all three studies to plan our next study; or should we ignore Study 2 and make our best guess about effect sizes from two studies that “worked?” It turns out that it makes a difference. If we want to run a study with 80% power just to detect the effect of the manipulation on mood (never mind the multiplicative effect of the manipulation on the final outcome that we expect mood to influence) we would need to plan a study that was 55% larger if we relied on the estimate from all three studies as compared to the estimate from just the two.

Additional Researcher Degrees of Freedom

A second reason why this requirement can be problematic is that until public preregistration becomes the norm for both original and replication studies, the use of failed manipulation checks as a reason for excluding studies from the published record can serve as an additional “researcher degree of freedom” that can increase rates of false positive findings in the literature. For instance, in one paper in the original series of studies on this effect, Strack, Schwarz, and Gschneidinger (1985) conducted studies with designs similar to ours. In at least one of the two studies where mood was expected to differ across conditions, the manipulation check was not significant (in the other, the statistics are somewhat ambiguous, though a p value less than .05 was reported)7, yet both studies were presented and interpreted. I’m not saying that this decision was necessarily wrong (as I noted, both manipulation checks were suggestive of an effect but appeared not to meet traditional thresholds for significance), but if rules about using manipulation checks to dismiss study results are applied inconsistently, then this additional researcher degree of freedom can lead to an overly positive picture of the evidence for an effect. And it’s important to remember that capitalizing on researcher degrees of freedom does not have to happen with any awareness on the part of the researchers. So the danger is that manipulation checks will only be interpreted as an indicator of study quality when the study fails to find the expected effect. Again, transparency with appropriately nuanced conclusions seems to be a better approach.

Sometimes the Replication is About the Manipulation

A third reason why we may not want to exclude studies with failed replication attempts from the literature is that sometimes the replicability of the manipulation itself can be questioned. As just one example, a recent registered replication report attempted to replicate a widely cited finding that relationship commitment affects relationship partners’ tendency to forgive relationship transgressions (Cheung et al. 2016). The original study tested this hypothesis by priming relationship commitment and then examining the effects of this manipulation on responses to hypothetical betrayals. Sixteen independent labs attempted to replicate the original effect, and these labs consistently failed to replicate both the focal result and the manipulation check. In a model of gracious reaction to a failed replication, the original author acknowledged the potential problems with the original manipulation (Finkel 2016), and overall, the replication attempt provided valuable information about the robustness of a theoretically important finding from the literature.

In this case, the fact that all sixteen labs failed to find support for the validity of the manipulation made conclusions about the replicability of the original manipulation straightforward, but imagine if this replication had been attempted by a single lab. It might have been easy to dismiss the failure as a function of the skill of the replicators.

Going back to our studies on mood and life satisfaction, the fact that some of our manipulation checks failed provides important information, especially given the state of knowledge about the effectiveness of the procedures that were used. For instance, in a prior study, we used data from almost a million people to test the extent to which weather conditions were associated with reports of life satisfaction (Lucas and Lawless 2013). Despite the extremely high power of this study we found no meaningful effects. Simonsohn (2015) discussed these results in his paper on how replications should be interpreted, and Schwarz and Clore (2016) challenged Simonsohn’s argument that our study could even be considered a replication of Schwarz and Clore (1983). The gist of their argument was that they, in the original study, were not interested in the effects of weather on life satisfaction but in the effects of mood on life satisfaction; weather was simply used as a convenient way to manipulate mood. Therefore, studies that do not assess mood (or that use mood induction procedures that do not successfully change people’s mood) tell us little about the robustness of the original finding.

I think that many of us have the intuition that our mood improves when the weather is nice. Indeed, Schwarz and Clore’s intuitions were so strong that they thought it unnecessary to pretest the effectiveness of this manipulation or to identify prior literature that supported their intuition. In their look back on these studies they noted:

In retrospect, we are surprised by how “painless” these experiments were. Unless our memories fail us, we did not conduct extensive pretests, were spared poor results and new starts, and had the good luck of “things falling into place” on the first trial (Schwarz and Clore 2003, 298)

and

We could comfortably rely on mental simulations of our own likely responses in setting up the procedures (Schwarz and Clore 2003, 298)

The problem is that there are good reasons to be skeptical that weather does affect mood, especially so strongly that it could result in effects as large as those found in the original study. As detailed in our paper (Lucas and Lawless 2013) and in a great blog post by Tal Yarkoni, it’s surprisingly difficult to find empirical evidence that weather is linked with mood. Most studies that have looked haven’t found much there. So an important goal of our paper was to test the replicability of the mood effect on life satisfaction and to test the replicability of manipulations like weather on mood. Both pieces of evidence help evaluate past research in this area.

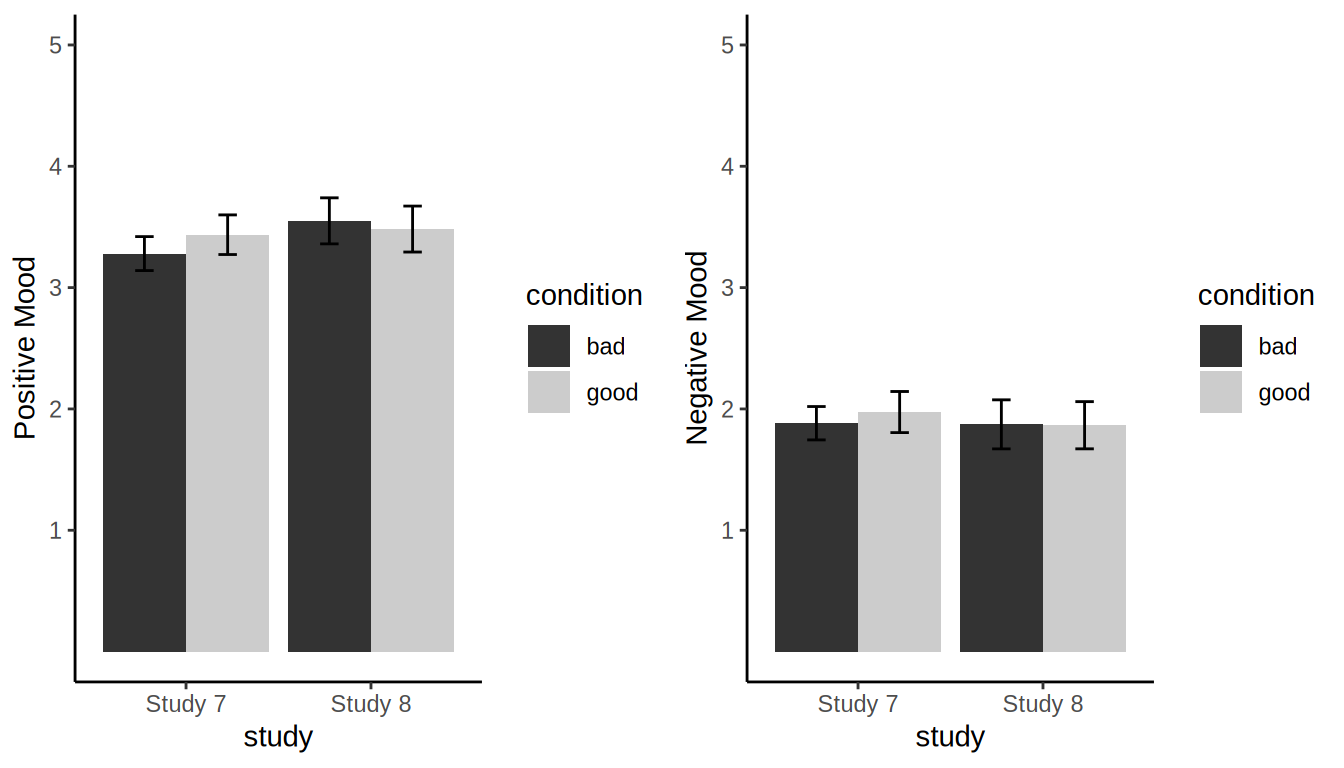

So did we find evidence that weather affects mood? Across two studies with much larger samples than the original, the answer was consistently “no”:8

It is absolutely true that because these mood inductions failed, these two studies cannot be used to answer the question of whether mood affects life satisfaction judgments. They can, however, be used to update our beliefs about the strength of existing evidence for such effects. An important brick in the wall of evidence used to support the idea that mood affects life satisfaction judgments comes from a single study that used weather as a manipulation. Until additional replications can be conducted, our results suggest that that particular brick may be weak.

Summary

It goes without saying that replication studies can only be interpreted if they are done well. Manipulation checks represent one way that the quality of the study and expertise of the investigators can be tested. However, a blanket rule that replications can be ignored—and perhaps even prevented from being published—if manipulation checks fail is problematic. At least in social and personality psychology, and perhaps even in psychology more broadly, the effectiveness of the specific procedures that we use is rarely so clearly established that a failed manipulation check unambiguously signals that a study was not competently conducted. Thus, in most cases, transparent reporting of all results, with appropriate caveats about the conclusions that can be drawn, is a better default.

References

Cheung, I., L. Campbell, E. P. LeBel, R. A. Ackerman, B. Aykutoğlu, Š. Bahník, J. D. Bowen, et al. 2016. “Registered Replication Report: Study 1 from Finkel, Rusbult, Kumashiro, & Hannon (2002).” Perspectives on Psychological Science 11 (5): 750–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616664694.

Finkel, Eli J. 2016. “Reflections on the CommitmentForgiveness Registered Replication Report.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 11 (5): 765–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616664695.

Lucas, Richard E., and Nicole M Lawless. 2013. “Does Life Seem Better on a Sunny Day? Examining the Association Between Daily Weather Conditions and Life Satisfaction Judgments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104 (5): 872–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032124.

Schwarz, Norbert. 1987. Stimmung Als Information: Untersuchungen Zum Einfluss von Stimmungen Auf Die Bewertung Des Eigenen Lebens. Berlin: Springer.

Schwarz, Norbert, and Gerald L. Clore. 1983. “Mood, Misattribution, and Judgments of Well-Being: Informative and Directive Functions of Affective States.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45 (3): 513–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.513.

Schwarz, Norbert, and Gerald L Clore. 2003. “Mood as Information: 20 Years Later.” Psychological Inquiry 14 (3-4): 296–303.

———. 2016. “Evaluating Psychological Research Requires More Than Attention to the N: A Comment on Simonsohn’s (2015) ‘Small Telescopes’.” Psychological Science 27 (10): 1407–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616653102.

Schwarz, Norbert, Fritz Strack, Detlev Kommer, and Dirk Wagner. 1987. “Soccer, Rooms, and the Quality of Your Life: Mood Effects on Judgments of Satisfaction with Life in General and with Specific Domains.” European Journal of Social Psychology 17 (1): 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420170107.

Simonsohn, Uri. 2015. “Small Telescopes: Detectability and the Evaluation of Replication Results.” Psychological Science 26 (5): 559–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614567341.

Strack, Fritz, Norbert Schwarz, and Elisabeth Gschneidinger. 1985. “Happiness and Reminiscing: The Role of Time Perspective, Affect, and Mode of Thinking.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (6): 1460–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.6.1460.

The opinions in this post are mine and may not reflect those of my co-authors.↩︎

Standardized mean differences in the range of 1 to 2.↩︎

Though the goal of the study was to test ideas about when people are likely to rely on their mood when making other judgments, and the original studies included more conditions than our replications did so the authors could examine this important theoretical question.↩︎

And if you need a little boost of optimism about the field, these studies—which were explicitly pitched as replications—were funded by the NIA (AG040175).↩︎

Note that there are a couple other studies that could be included in the top section, but that did not report enough information to calculate effect sizes. Our attempts to calculate these effects are described here. Also note that the estimates reported in the plot are from a random-effects meta-analysis; the scripts on our OSF page can be modified to test alternative meta-analytic models.↩︎

And because this post is written in Rmarkdown, you can get the code and data by visiting the github site where this blog is hosted.↩︎

In both studies a 2 X 2 design was used, and the mood effect was only expected in one condition of the other manipulated factor. In Study 2, the only manipulation check statistic reported was for the effect of mood in the condition that was expected to work, and the p-value was .06. In Study 3, the only manipulation check statistic reported was for the interaction.↩︎

Full disclosure: running these studies was challenging, and identifying days that differed only in weather conditions was difficult. For a full discussion of these difficulties and the implications for our results, please take a look at our paper.↩︎